The world's coral reefs are under unprecedented threat from rising ocean temperatures. As marine heatwaves become more frequent and intense, the delicate symbiotic relationship between corals and their algal partners is breaking down. This phenomenon, known as coral bleaching, has devastated reef systems across the globe. In response to this crisis, scientists have launched an ambitious global initiative: the Coral Gene Bank - a comprehensive backup plan for heat-resistant algal strains that could hold the key to saving our reefs.

Beneath the turquoise waters of tropical oceans lies one of Earth's most biodiverse ecosystems. Coral reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor yet support nearly 25% of all marine species. The secret to their success lies in their partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. These photosynthetic organisms live within coral tissues, providing essential nutrients through photosynthesis while receiving shelter and compounds necessary for their growth in return. When water temperatures rise just 1-2°C above normal summer maxima, this fragile alliance collapses.

The current bleaching crisis represents more than just an ecological disaster - it threatens the livelihoods of half a billion people who depend on reefs for food, coastal protection, and tourism revenue. Recent mass bleaching events have affected over 75% of tropical reefs worldwide, with mortality rates reaching 50% in some regions. Traditional conservation methods like marine protected areas are no longer sufficient against the relentless march of climate change. This realization has spurred researchers to develop innovative solutions that could buy time for reefs while global carbon emissions are brought under control.

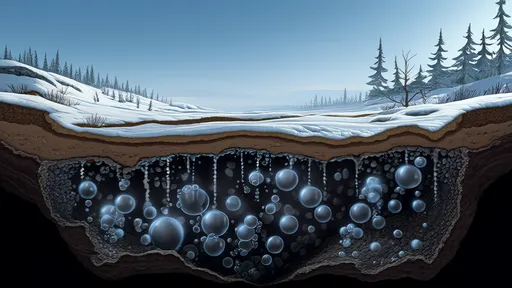

At the forefront of these efforts is the Coral Symbiont BioBank, a collaborative project involving marine research institutions across fifteen countries. The facility houses living cultures of over 500 distinct strains of Symbiodiniaceae (the algal family that partners with corals), carefully preserved in state-of-the-art cryogenic storage systems. What makes this collection unique is its focus on heat-tolerant variants collected from reefs that have naturally survived repeated bleaching events.

Dr. Elena Martinez, lead scientist at the BioBank's Hawaiian facility, explains: "We're not creating anything new in a lab - we're identifying and preserving what nature has already evolved. Some coral populations have persisted in warmer waters because their algal partners possess remarkable resilience. By studying and safeguarding these biological treasures, we're creating an insurance policy for reef ecosystems."

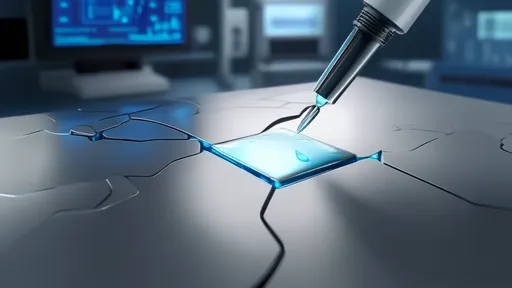

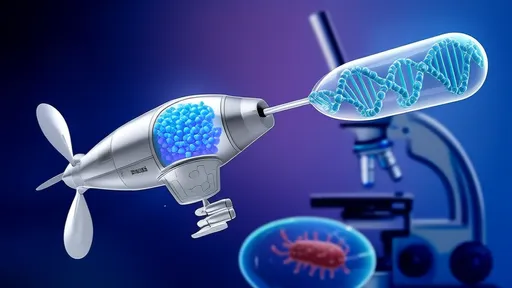

The collection process is both scientifically rigorous and logistically challenging. Teams of divers collect small coral samples from thermally resilient reefs, often in remote locations. Back in laboratory settings, researchers carefully isolate the algal symbionts and subject them to rigorous thermal tolerance testing. Only the hardiest strains make it into the permanent collection, where they're preserved using cryopreservation techniques that maintain their viability for decades.

One particularly promising discovery came from the Persian Gulf, where corals survive summer temperatures that would kill most tropical reef species. Researchers identified several algal strains capable of photosynthesizing efficiently at 36°C - nearly 5°C above the threshold that triggers bleaching in most corals. Similar heat-resistant symbionts have been found in American Samoa's Ofu Island lagoon, where daily temperature fluctuations have created unusually resilient coral communities.

The BioBank serves multiple critical functions beyond simple preservation. Scientists are sequencing the genomes of these algal strains to identify the genetic markers associated with thermal tolerance. This research has already revealed fascinating adaptations, including enhanced antioxidant systems that protect against heat-induced cellular damage and unique lipid compositions that maintain membrane fluidity under thermal stress.

Perhaps most importantly, the preserved strains are being used in assisted evolution experiments. Coral larvae are inoculated with different algal combinations to test which partnerships show the greatest climate resilience. Early results suggest that some heat-tolerant symbionts can be successfully introduced to coral populations that have lost their native partners during bleaching events. While not a silver bullet, this approach could significantly improve survival rates during marine heatwaves.

The project faces significant challenges, both technical and ethical. Some conservation biologists worry that introducing non-native algal strains could disrupt local ecosystems or reduce genetic diversity. There are also concerns about creating a false sense of security that might divert attention from addressing the root cause of reef decline - climate change. BioBank researchers emphasize that their work complements rather than replaces traditional conservation and emissions reduction efforts.

Logistical hurdles abound as well. Maintaining living algal collections requires sophisticated infrastructure and constant monitoring. The BioBank has established redundant facilities across multiple continents to safeguard against natural disasters or equipment failures. Funding remains an ongoing concern, as the project relies on a patchwork of government grants and private donations.

Despite these challenges, the Coral Symbiont BioBank represents one of the most promising avenues for reef conservation in an era of rapid climate change. As Dr. Martinez notes, "We're not just preserving algae - we're preserving options. When future marine biologists look back at this critical juncture, they'll judge us not just by the problems we identified, but by the solutions we had the foresight to preserve."

The next phase of the project will focus on scaling up restoration efforts. Pilot programs in the Great Barrier Reef and Caribbean are testing methods for large-scale introduction of resilient algal strains to wild coral populations. Simultaneously, researchers continue to scour the world's oceans for new heat-adapted variants, particularly in understudied regions like the Red Sea and Southeast Asia.

As ocean temperatures continue to rise, the work of the Coral Gene Bank takes on increasing urgency. While the ultimate solution to the coral crisis requires global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this innovative preservation strategy offers hope that the world's reefs might survive long enough to see a more stable climate future. In the delicate dance between coral and algae that has sustained marine ecosystems for millennia, scientists are now working to choreograph a new partnership - one that can withstand the heat of the Anthropocene.

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025