The field of aging research has witnessed a paradigm shift with the emergence of epigenetic reprogramming as a potential tool to reverse cellular aging. Recent breakthroughs in partial reprogramming techniques have demonstrated that controlled exposure to Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) can reset epigenetic markers without completely erasing cellular identity. This delicate balance between rejuvenation and maintaining cellular function has sparked intense investigation into defining the precise safety thresholds for epigenetic erasure.

Understanding the Epigenetic Clock

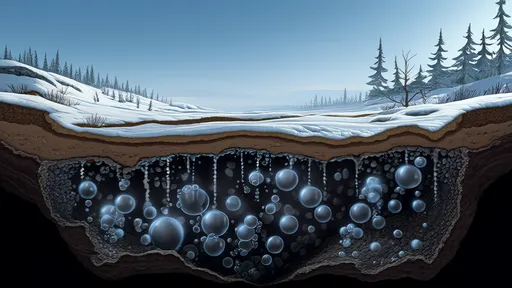

Epigenetic clocks have become the gold standard for measuring biological age, tracking chemical modifications to DNA that accumulate over time. These methylation patterns serve as molecular fingerprints of aging, with certain sites becoming hypermethylated while others lose methylation in a remarkably predictable pattern. Researchers now believe these clocks don't merely mark time but may actively participate in the aging process itself, making them prime targets for intervention.

The revolutionary work of Dr. Shinya Yamanaka, who discovered how to reprogram adult cells into pluripotent stem cells, unexpectedly provided tools to manipulate these aging markers. However, full reprogramming completely wipes a cell's epigenetic memory - an unacceptable outcome for anti-aging therapies where maintaining tissue-specific function is crucial. This realization birthed the concept of partial reprogramming, where brief, controlled exposure to reprogramming factors could potentially rejuvenate cells without losing their identity.

The Safety Threshold Challenge

Determining the precise duration and intensity of reprogramming factor exposure that yields optimal rejuvenation without compromising cellular function represents perhaps the most significant challenge in the field. Early animal studies demonstrated that continuous expression of Yamanaka factors led to teratoma formation and loss of tissue organization, while too little exposure showed negligible effects. The sweet spot appears to be a matter of days rather than weeks, but varies significantly between cell types and tissues.

Researchers at the Salk Institute made headlines when they showed that cyclic induction of OSKM factors in progeroid mice could extend lifespan by 30%, with treated animals showing improved organ function and delayed onset of age-related pathologies. Importantly, these mice didn't develop tumors, suggesting the protocol stayed within safe parameters. Subsequent work revealed that the treatment didn't completely reset methylation patterns to embryonic levels, but rather reversed many of the age-associated changes while preserving cell-type specific methylation.

Biomarkers of Safe Reprogramming

The scientific community has identified several biomarkers that help define the safety window for epigenetic reprogramming. Transcriptomic analysis reveals that beneficial effects occur when cells transiently activate embryonic pathways without fully committing to pluripotency. At the epigenetic level, safe reprogramming appears to preferentially target regions known as "aging methylation sites" while largely sparing developmental and imprinted genes.

Cellular senescence markers provide another important safety gauge. Effective partial reprogramming reduces p16INK4a and SA-β-galactosidase positive cells without eliminating them entirely - complete eradication of senescent cells can impair wound healing and tissue repair. The maintenance of proper chromatin organization serves as an additional checkpoint, as excessive reprogramming leads to visible disruption of nuclear architecture and lamina organization.

Tissue-Specific Considerations

Emerging evidence suggests different tissues may require distinct reprogramming thresholds. The liver, for instance, appears particularly responsive to epigenetic rejuvenation, with even brief reprogramming yielding significant functional improvements. In contrast, neural tissues show more gradual responses, possibly due to their lower turnover rates. Cardiac tissue presents unique challenges, as excessive reprogramming can disrupt the delicate electrophysiological properties of cardiomyocytes.

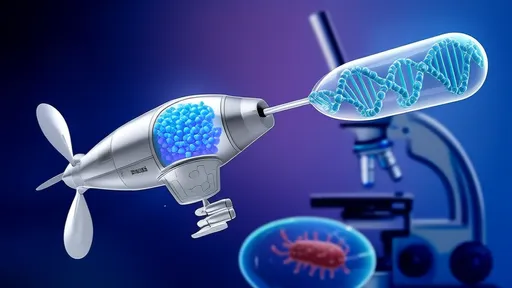

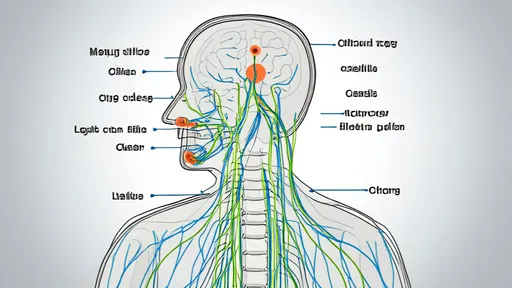

The blood-brain barrier adds another layer of complexity for systemic treatments. While it protects neural tissue from uncontrolled reprogramming, it also necessitates specialized delivery methods for brain rejuvenation. Researchers are exploring various viral vectors and lipid nanoparticles to achieve tissue-specific targeting, with some success in preclinical models.

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite promising results, significant hurdles remain before epigenetic reprogramming can be safely translated to humans. The field still lacks comprehensive long-term safety data, particularly regarding potential effects on the immune system and stem cell niches. There's also concern that partial reprogramming might inadvertently activate dormant oncogenes or disrupt tissue homeostasis in unpredictable ways.

Next-generation approaches aim to refine the process further. Some groups are developing small molecule alternatives to the Yamanaka factors that could offer better temporal control. Others are exploring the use of RNA or protein delivery instead of genetic modification to achieve transient reprogramming. The ultimate goal remains defining precise, personalized reprogramming protocols that can safely roll back epigenetic age while preserving cellular function and identity.

As research progresses, the scientific community remains cautiously optimistic that safe epigenetic rejuvenation may one day become a reality. However, experts emphasize that rigorous preclinical testing and careful dose optimization will be essential to avoid the pitfalls that have derailed previous anti-aging interventions. The coming years will likely see continued refinement of these techniques as we move closer to understanding the true potential and limitations of resetting our biological clocks.

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025