In the shadow of our rapidly digitizing world, an invisible treasure trove lies buried within the drawers and landfills of urban landscapes: discarded smartphones. While most consumers view old devices as mere electronic waste, a quiet revolution is unfolding in metallurgical laboratories and industrial parks—where chemists and engineers are perfecting the art of extracting platinum group metals (PGMs) from these forgotten relics. This urban alchemy doesn’t just promise profitability; it’s rewriting the rules of sustainable resource management.

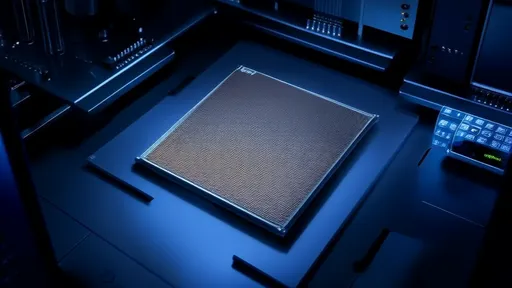

The staggering volume of global e-waste—approximately 53 million metric tons annually—contains concentrations of PGMs that often exceed those found in primary ores. A single metric ton of printed circuit boards harbors between 80 to 150 grams of palladium and 200 to 250 grams of silver, alongside trace amounts of platinum and rhodium. These figures become economically compelling when considering that over 1.5 billion smartphones are discarded yearly, their metallic souls waiting to be liberated through advanced recovery techniques.

Traditional mining operations pale in comparison to the efficiency of urban ore harvesting. Extracting one ounce of platinum from virgin deposits requires processing 10 tons of ore, consuming enough energy to power a mid-sized home for six months. Contrast this with smartphone recycling, where the same ounce can be obtained from about 14,000 devices while reducing energy expenditure by 85%. The carbon footprint differential is equally striking—PGM recovery from electronics generates merely 5% of the greenhouse gases associated with conventional mining.

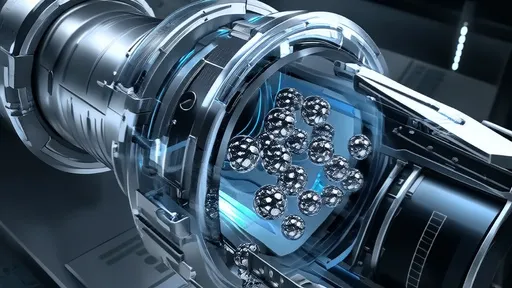

Modern hydrometallurgical processes have achieved remarkable finesse in separating these precious metals. At specialized facilities like Belgium’s Umicore plant, a proprietary blend of high-temperature smelting and chemical leaching recovers up to 95% of PGMs from complex electronic waste streams. The operation resembles a high-tech distillery, where smartphone components are systematically broken down into elemental constituents through a series of precisely controlled reactions. What emerges isn’t just raw metal, but certified conflict-free materials ready for reuse in catalytic converters, medical devices, and next-generation electronics.

The geopolitical implications are profound. With over 70% of global PGM supply currently controlled by just two nations (South Africa and Russia), urban mining offers democratic access to these critical resources. Cities like Tokyo and San Francisco now yield higher concentrations of recyclable PGMs per square kilometer than many active mines. This geographical shift is prompting nations to reevaluate their strategic resource policies—the Japanese government’s "Urban Mine Initiative" has already stockpiled recovered metals equivalent to 16% of their annual industrial demand.

Yet significant barriers persist. Consumer participation remains the weakest link in the recovery chain, with only 17% of discarded electronics entering formal recycling streams. The remainder either gathers dust in households or disappears into informal recycling networks where primitive acid baths extract gold while poisoning workers and ecosystems. Addressing this requires not just awareness campaigns but systemic redesign—modular smartphones like Fairphone are pioneering easier disassembly, while blockchain projects now track metals from recovery to reuse, creating verifiable green supply chains.

As the circular economy matures, the financial sector has taken notice. London Metal Exchange recently introduced contracts for recycled PGMs, allowing traders to hedge against traditional mining disruptions. Venture capital flows into urban mining startups have grown twelvefold since 2018, with companies like BlueOak Resources and Redwood Materials achieving unicorn status by perfecting electrochemical separation methods. Their innovations promise to push recovery rates beyond 98% while eliminating toxic byproducts—a quantum leap from the mercury-laden practices still prevalent in informal sectors.

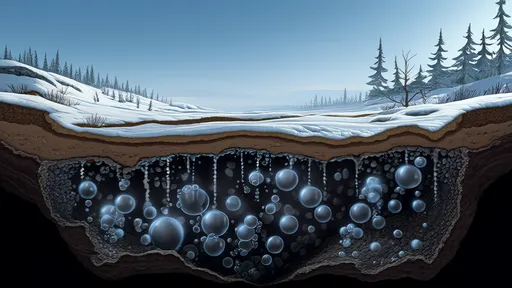

The environmental calculus makes this transition imperative. Producing platinum from recycled sources requires just 7% of the water needed for primary production—a critical advantage as water scarcity intensifies globally. When accounting for the avoided destruction of biodiverse regions like South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex (where 80% of virgin PGMs originate), the conservation benefits multiply exponentially. Each ton of urban-mined PGMs preserves approximately 15,000 square meters of pristine habitat from open-pit mining devastation.

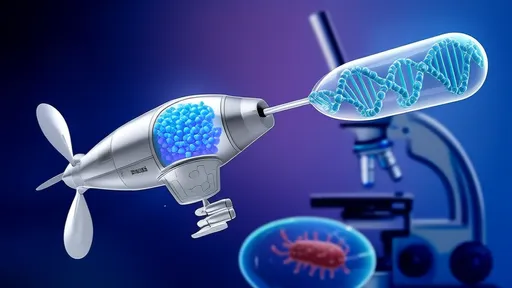

Looking ahead, the convergence of nanotechnology and recycling holds particular promise. Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed graphene-based nano-filters capable of selectively capturing PGMs from diluted acidic solutions—a method that could revolutionize small-scale recovery operations. Meanwhile, Australia’s national science agency CSIRO has pioneered biological recovery using specially engineered bacteria that accumulate precious metals, offering an eco-friendly alternative to traditional smelting.

This urban alchemy represents more than technical innovation; it signals a fundamental reimagining of cities as dynamic resource reservoirs. As the Internet of Things expands and device miniaturization continues, the concentration of valuable metals in urban waste streams will only intensify. The smartphones we casually discard today may well become the foundation for tomorrow’s sustainable industries—their once-hidden treasures transformed through human ingenuity into the currency of a cleaner future.

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025

By /Aug 5, 2025